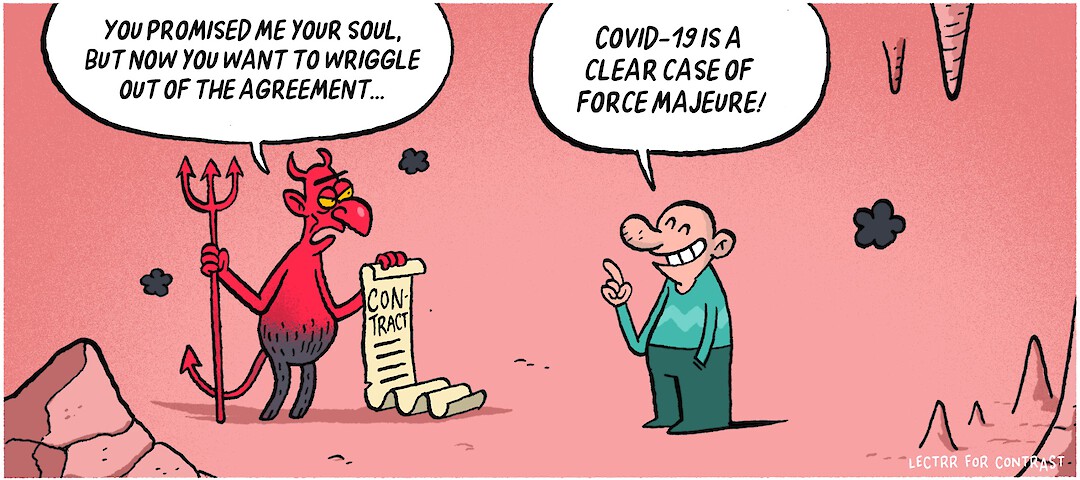

In the Picture

Covid-19’s impact on commercial contracts: Force majeure, not just a standard clause

July 2020Imagine…

You are the head of a major retail chain, with stores at unique locations throughout the European Union.

In several member states the government compelled you to temporarily close your stores in order to help impede the further spread of the Covid-19 virus. In the meantime, most of the stores are open again, but the flow of returning customers has been anaemic at best.

You have already drawn upon the financial support measures offered by various governments, but you fear that this won´t be enough.

Not only are you having problems with promptly paying your suppliers, but the monthly commercial lease at many locations is becoming prohibitively expensive. A number of co-contracting parties are threatening to start legal proceedings.

Moreover, the fear of a second wave of the coronavirus and new lockdown measures is increasing. Fortunately, all of your contracts now always contain a standard force majeure clause, so you are fully covered . . . or are you?

A brief clarification.

The corona crisis is having a huge impact on business and endangering the execution of many on-going commercial contracts, e.g. due to the obligatory closures that were imposed by the government in several countries.

The law of obligations is a national law that has not (yet) been harmonised at the European level and thus is regulated by each EU member state independently. In all member states there applies the basic principle of “pacta sunt servanda”. Agreements must be kept. At the same time, all member states also acknowledge force majeure as an exception to this rule. Force majeure releases a party (temporarily or definitively) from its contractual obligations. In that event, in principle the obligations of the opposite party are suspended or annulled as well.

To determine whether force majeure is actually present or not, an assessment must be conducted on a member state by member state and case by case basis. In the first instance, the provisions of the contract itself are generally of decisive importance in this assessment.

Many commercial contracts do contain force majeure clauses or hardship clauses. However, the scope and wording of such clauses can vary widely.

If the contract does not offer any answers (or any satisfactory ones), the general principles of supplementary law apply on the basis of the applicable national law.

Traditionally, the concept of force majeure has been strictly construed. As a rule, force majeure exists only when (i) unforeseeable and unavoidable circumstances that are not imputable to the fault of a party (ii) make it (absolutely) impossible for that party to fulfil its obligation(s).

There is usually no force majeure if the fulfilment of contractual obligations has merely become more onerous or difficult. In some member states, the contracting parties in such a situation can nevertheless be obliged to renegotiate the contract on the basis of the hardship doctrine. In the absence of an explicit contractual clause, however, the hardship doctrine is not accepted per se in all member states. This is presently the case in Belgium, for example – although there are plans to introduce the doctrine as part of an upcoming reform of the law of obligations.

If there is no force majeure or hardship, and a party nevertheless does not appear to be fulfilling specific contractual obligations, the question arises whether the other party can claim damages on this basis, or suspend its own contractual obligations in whole or part, e.g. invoking the objection of non-fulfilment. In most member states, the rule is that the other party may not exercise its contractual rights in bad faith or in a manifestly unfair way.

So if the retail chain wants to review its contractual obligations vis-à-vis its suppliers and lessors within the Covid-19 context, it will have to verify case by case:

- What law applies to a particular contract;

- Whether the contract contains language that regulates its own suspension, termination or adaptation (e.g. force majeure or hardship clauses);

- What are the concrete conditions of application and consequences of such clauses; and

- If necessary, revert to the general principles of supplementary national law.

In the absence of a clear contractual clause, one often cannot unambiguously answer the question of the concrete liability of the contracting parties and which party ultimately must bear the risk and the suffered damage.

In any case, the Covid-19 crisis demonstrates that force majeure clauses merit special attention.

Concretely:

- Contracts are governed by the national law of the member states. Legal concepts such as force majeure and hardship are not harmonised at the European level. It is important to verify what law applies in each individual case.

- It is best not to deal with contractual provisions about the suspension, termination or adaptation of the contract via a purely standard clause (so-called “boilerplate”). The concrete wording of such provisions is crucial for determining the impact of unforeseeable or unforeseen circumstances on the contract. In the absence of an unambiguous clause, it will often be impossible to clearly define the concrete position of the contracting parties in a typical situation of force majeure.

Want to know more?

- Information about federal support measures in Belgium in connection with the coronavirus can be found via https://financien.belgium.be/nl/ondernemingen/steunmaatregelen-betreffende-het-coronavirus-covid-19 and via https://economie.fgov.be/nl/themas/ondernemingen/coronavirus/coronavirus-informatie-voor

- Information about the Flemish measures for companies, via https://www.vlaanderen.be/gezondheid-en-welzijn/gezondheid/gezondheid-en-preventie-tijdens-de-coronacrisis/steunmaatregelen-voor-zelfstandigen-en-ondernemers-die-schade-lijden-door-de-corona-crisis and via https://www.vlaio.be/nl/begeleiding-advies/moeilijkhedencoronavirus/specifieke-maatregelen-mbt-het-coronavirus/coronavirus

- Information about the measures of the Brussels-Capital Region can be found via https://1819.brussels

- Information about the Walloon measures can be found via https://www.1890.be